The CEO of Rystad Energy was the keynote speaker at the GCE NODE Top Leader Forum in Kristiansand Thursday night. Approximately 60 top executives from cluster companies participated.

As always, Rystad presented an in-depth analysis based on one of the world’s most comprehensive data bases for the energy sector. He described pathways to various global warming scenarios, ranging from 1.4 to 2.2 degrees.

“The 1.4 and 1.5 scenarios are too demanding. They would require a massive but short peak period for the solar energy industry. We would have to build hundreds of factories very quickly, and many of them would be superfluous within a few years. This scenario does not make sense from a business perspective, and consequently it will not happen,” says Rystad.

Overall, renewable energy sources will replace fossil fuels in the energy mix, and the speed of renewable deployment will determine how fast fossil fuels can be phased out.

“Oil and gas will be phased out, not as a result of political will, but at the hand of market forces. Fossil energy sources will be unable to compete with solar and wind energy, which become increasingly cheaper due to scale and innovation,” says Rystad.

Hundreds of gigawatts of solar power capacity are set to be added during this decade. And yearly installation of wind turbines could double every four years, reaching 350 GW in the early 2030s, which is needed for the 1.6 degrees scenario. Battery cell capacity could grow sufficiently to provide backup for the intermittency of solar and wind generation.

Renewable power generation is already economically competitive most places, and the COP26 agreement to phase out subsidies in support of fossil fuels will further strengthen the competitiveness of renewables and hence the speed of deployment.

However, supply chain challenges and grid balancing issues could slow the deployment of many renewable energy projects.

“Given the accelerated deployment of wind and solar projects, demand for power from fossil fuels will decline significantly in coming years. We expect global demand for oil to decrease from the current 100 million barrels per day, to 61 million barrels per day in 2040,” says Rystad.

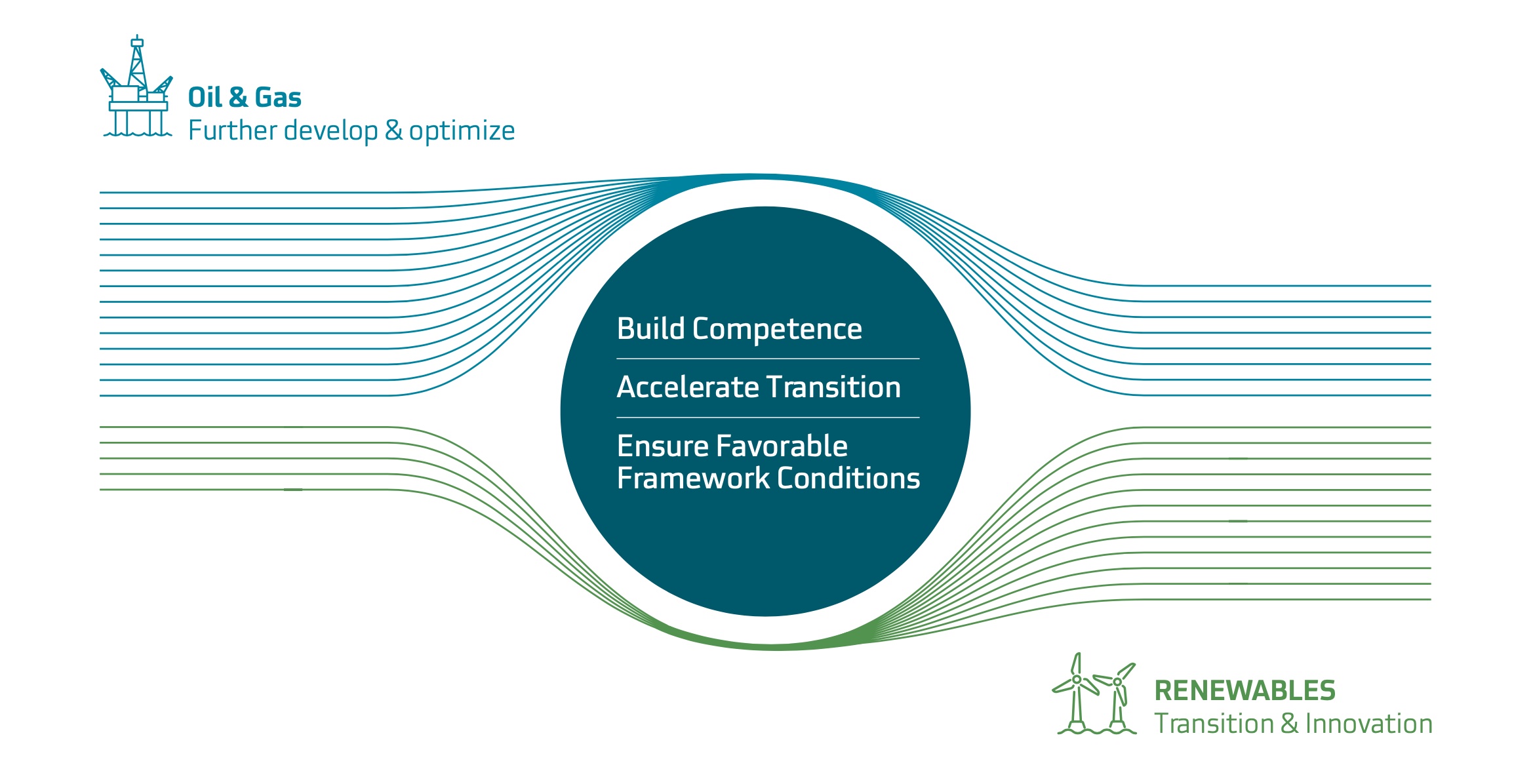

So, how should suppliers to the oil and gas industry respond to this scenario?

“Oil and gas will always be a cyclical industry. Thus, it makes sense for the supplier industry to diversify, especially into renewable energy. Still, oil and gas will remain a very large industry which will provide lots of future business opportunities. Even if global demands drops to 61 million barrels in 2040, tens of thousands of wells have to be drilled and thousands of new oil fields must be identified, developed and opened for production in years to come,” says Rystad.

The growth of solar and wind energy will change the energy mix completely. According to Rystad Energy, renewable energy sources will supply 77 per cent of global energy in 2050.

How fast can an energy system change? “Very fast,” according to Rystad, who illustrated how consumption of coal dropped a whopping 97 percent between 1958 and 1973.

“Ford has already closed four fossil car factories. And the sale of electric vehicles in Germany has spiked from single digit to more than 20 per cent,” explained Rystad.

He stressed that future estimates are of course associated with uncertainty, illustrated by the fact that current output of oil and gas is 60 per cent higher than the most optimistic prediction 20 years ago.

The Norwegian Continental Shelf will be the site for massive new developments in coming years, with the number of new fields more than tripling compared to the last few years.

“Production in the Norwegian sector has a very low environmental footprint. Consequently, Norway should produce gas as long as there is demand for gas, that would be best for the environment. If Norway were to stop producing gas, the demand for gas would be met by producing countries which have up to ten times larger emissions from their production. The same principle applies to oil production, but here the difference between production in Norway and elsewhere is not as significant.